Enríquez de Valderrábano

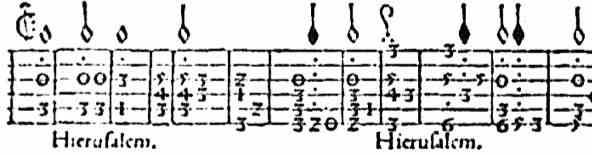

Hierusalem convertere ad dominum [Ortiz]

Silva de sirenas (1547), fol. 32v

va057

| Source title | Lamentacio[n], si que se a de tañer co[n]forme al te[m]po su entonacio[n] es segu[n]da e[n] tercero traste. Segu[n]do grado. |

|---|---|

| Title in contents | Lamentación. Hierusalem en el segundo grado. Ortiz. |

| Text incipit | Hierusalem Hierusalem |

Music

Category intabulation

Genre motet

Fantasia type

Mode 1

Voices 5

Length (compases) 66

Vihuela

Tuning E

Courses 6

Final IV/0

Highest I/6

Lowest VI/3

Difficulty medium

Tempo medium

Song Text

Language LA

Vocal notation texted staff notation

Commentary

Intabulation by Valderrábano of a motet in five voices that he attributes to Miguel Ortiz. Gil transcribes the piece for a vihuela in A but Valderrábano specifies that the first note of the mensural soprano voice is a d’, located on II/3 and thus a vihuela in E. The musical style is non-imitative, and appears to recall a native Spanish style rather than polyphony in the Franco-Flemish style. The text is the final supplication of a Lamentation for Maundy Thursday, Matins, First Nocturn. Together with va056, this piece is attributed to Miguel Ortiz, a composer today unknown other than a reference to a Miguel Ortiz in the employ of Rodrigo de Vivar y Mendoza, I conde del Cid and I marqués del Cenete (Guadalajara 1466?–Valencia 1523) (sol2009, 7) see also https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rodrigo_D%C3%ADaz_de_Vivar_y_Mendoza.

Concerning Valderrábano’s music Manuel de Sol comments: “A pesar de que no se trata de un arreglo de la lamentación completa, es posible identificar en esta transcripción algunos diseños melódicos propios de la tradición hispana. La gran mayoría de los compositores renacentistas utilizaron como cantus firmus en este repertorio un tonus lamentationum autóctono. Es decir, las melodías del canto llano para las lamentaciones estaban tan estrechamente arraigadas en este género que los polifonistas recurrieron a dichas entonaciones —propias de sus tradiciones locales, regionales o institucionales— para usarlas como melodías preexistentes en la elaboración de sus composiciones polifónicas. Entre las numerosas prácticas litúrgicas locales e institucionales vigentes en Europa durante la Edad Moderna, el tono romano y el tono hispano dominaron la praxis melódica de este género. Por ejemplo, en la lección incompleta de Ortiz es posible identificar el initium melódico característico de los toni lamentationum hispanos (Re-Fa-Sol/Mi-Sol-La/La-Do-Re) en la voz más grave del acompañamiento de la vihuela”. [Although this is not a complete arrangement of the lamentation, it is possible to identify in this transcription some melodic designs typical of the Hispanic tradition. The great majority of Renaissance composers used a native tonus lamentationum as cantus firmus in this repertoire. That is to say, the plainchant melodies for lamentations were so closely rooted in this genre that polyphonists drew on such intonations - proper to their local, regional or institutional traditions - to use them as pre-existing melodies in the elaboration of their polyphonic compositions. Among the many local and institutional liturgical practices in Europe during the Modern Age, the Roman and Hispanic tones dominated the melodic praxis of this genre. For example, in Ortiz's incomplete lesson it is possible to identify the melodic initium characteristic of the Hispanic toni lamentationum (Re-Fa-Gol/Mi-Sol-La/La-Do-Re) in the lowest voice of the vihuela accompaniment.] (sol2009, 8-9).

Literature

Recordings

Song Text

Hierusalem, Hierusalem convertere ad Dominum Deum tuum.

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, return to the Lord your God.